Ordways: A Family of Labor - Part 1 of 2

Dad’s life lessons in the yard and in the mill

In the book "The Fourth Turning" (1997), author Strauss discusses the four seasons or turnings: High, Awakening, Unraveling, and Crisis, which identify recurring generational archetypes in the U.S. They are driven by institutional decline, growing individualism, and that turns into (cultural) revolution. The process is complete when an old social order is discarded and replaced with a new one.

Similarly, there is a cyclical theory that hard times create strong men, strong men create good times, good times create weak men, and weak men create hard times.

There are many ways to analyze this theory in relation to Christianity and Masculinity, but I’ve cut out 1,000 words to keep this piece focused.

For Ordways, the four cycles are completely foreign to them. Good times are never taken for granted, and hard times are where life’s best lessons are learned. In fact, voluntary hardship is mandatory to pass into manhood. I attribute such resistance to the easy life to our family’s culture, derived from The Agrarian Tradition, which has many virtues, one deeply rooted in labor.

It’s in the blood

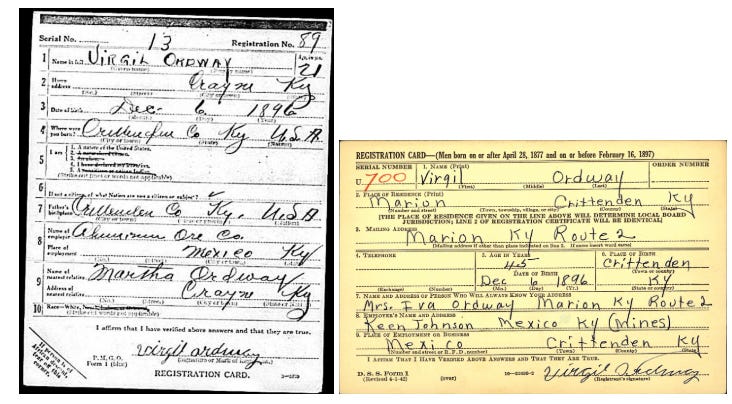

In another Substack piece, I trace the Ordway’s lineage back to indentured servitude, where James became one of the first settlers of Newbury, Massachusetts. One hundred fifty years later, Sgt John Ordway would journal for 863 days straight on the Lewis & Clark Expedition as they traveled over 8,000 miles by canoe, horseback, and foot. His relocation to New Madrid and the subsequent earthquakes would push the Ordways into the Black Patch of western Kentucky, where they lived for the next 150 years. It’s a place where the tobacco wars would be fought during the childhood of my great-grandfather, Virgil.

Four Generations of Hard Men – No Turning, No Cycles

I can only describe western Kentucky as a hard-scrabble place. Much like Appalachia, the Industrial Revolution came and went with little participation from them. A few Ordways owned livery stables, an ice company, and a machine shop, but the vast majority were small-scale farmers.

According to my research, Ordways rarely owned more than 100 acres. When you consider the size of their families (8-12), it was imperative to live frugally in order to acquire more land that would ultimately be split up and worked by the children. There was no real wealth accumulation for the farmer, as a job begets a job each generation, unless one had owned slaves 50 years or more earlier.

Crittenden became 99% white within 5 years after the Civil War. For those who had money, they would transition their business during the second industrial revolution with mechanization, or as I like to call it, the rise of the machines (a subtitle of Terminator 3). Small-scale farmers like Virgil got pushed aside. To survive, he took one foot out of farming and put it in the fluorspar mines (‘spar is what locals call it), whereas the Illinois-Kentucky District produced 40% of the world’s fluorite, a desirable mineral used in the steelmaking process.

Eastern Kentucky is the more renowned part of the state due to the Harlan County War, as well as numerous Appalachian studies conducted by colleges, universities, and the federal government. There, coal miners fought to organize unions, but at the same time, in western Kentucky, the local paper, the Crittenden Press, had no coverage of labor strife. Any small farmer with debt during the time of the Great Depression was crushed, so a job from FDR’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) was a savior for many in the area. Even after decades of work, Virgil was still a groundsman, but with federal labor laws finally in place, the spar mines would be unionized as they hit record production during World War II.

Like his dad, Papaw Hollis would also have a hardscrabble upbringing. Luckily, his six-month-younger second cousin, Bruce, is still alive (93) to talk about their early years. Bruce grew up across the street from Hollis and was born at home because the county didn't have a hospital. There was no electricity, so they used Aladdin lamps to light the house. Lanterns were required to find the outhouse in the dark since there was no plumbing. Heat came from coal, and ice boxes were the norm. Most meals consisted of beans, and sometimes mustard was added to ‘fancy them up.’ Bruce used cardboard as inserts when he wore holes through his shoes. Hard times indeed.

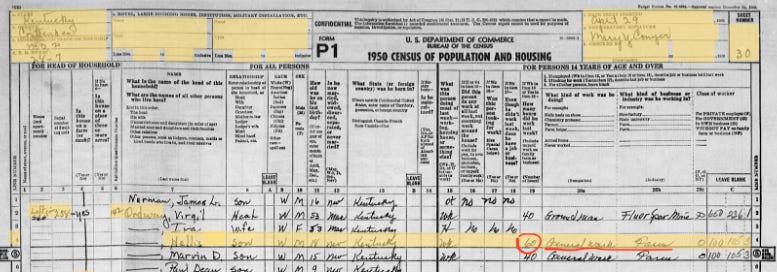

Work ethic is hardwired into the Ordway ethos through parenting. It was no surprise to me, and it garnered a chuckle to pull up the 1950 census and see the 18-year-old papaw Hollis listed as working on the farm 60 hours a week, as his dad labored in the mines.

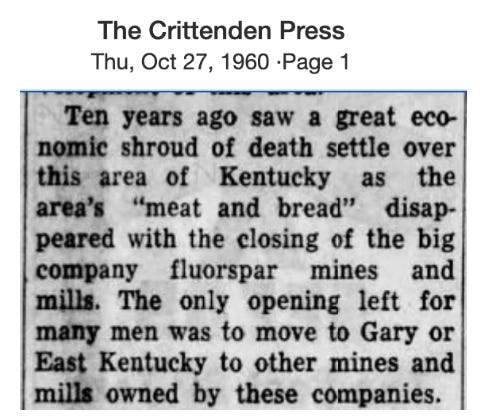

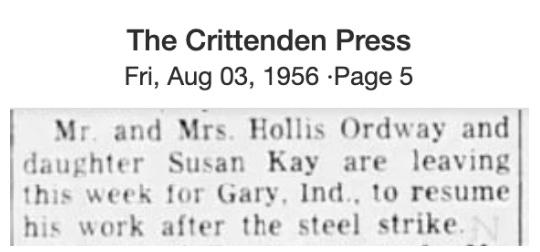

After returning from the Korean War, Papaw observed that western Kentucky remained unchanged. Big Steel lobbied the federal government to import (mostly from China), so the fluorspar mines were crushed. Another one of FDR’s WPA programs would support road building, and my papaw’s generation would use them to leave (often called Hillbilly Highways). Ironically, he would work for one of the companies that helped destroy mine production in the U.S, which ceased all production in 1985, the year I was born.

Luckily for Papaw, he was part of the second wave of the Great White Migration, a subject that has not been fully explored. By then, unions such as USW Local 1066 were already strong when he landed employment at U.S. Steel’s Sheet & Tin Mill at Gary Works. The 1959 Great Steel Strike was the largest in U.S. history. It was a battle over work rules that could result in reduced hours or job cuts for employees assigned to a particular task. The strike that occurred just a few years earlier involved 500,000 nationwide. The EPA did not exist during his early years at the mill, so the pollution of both water and air was terrible for steelworkers' health. (And it still is.)

After 33 years in the mill, Papaw would return to Kentucky, a common practice for southerners (both black and white) who acknowledged that, culturally, the North was never home. With family roots now planted in the north, Mamaw saw it differently, but she would not be the final decision-maker. Either way, they gifted the house to my Dad and uncle.

Dad would also be exposed to the family grind during childhood. The house and yard would reflect Kentucky transplants, complete with a large yard, a tin shed, a burn barrel, and a seasonal garden. Dad also entered the Gary Works Sheet & Tin Mill, but the 1980s were unkind to labor, with imports, automation, and consolidation leading to permanent job losses. Dad would be laid off but gained employment a county over at Metro Metals, a steel finishing plant. According to one of his friends, when U.S. Steel called back to rehire, he took a pass.

Dad would leave the USW but would join the International Longshoreman’s Association (ILA). He was not one to promote brands but displayed his union sticker on his truck with pride. Even though his work environment was clean, it’s well known that shift-work can still wreak havoc on the body. Dad never complained. An informal rule of Ordway parenting is “no whining” regardless of circumstances. Even with a punch card, Dad believed in showing up early and leaving late for all things in life, including work – the opposite of a South’s liesurely cadence.

During a few fishing trips, his friends would drop me off at the mill as he finished up the midnight shift, so we could take off to the small lakes of Wisconsin or Michigan. I saw exactly what my Dad did all day (and night) long and distinctly remember him stating, “You don’t ever want to be in this line of work.” As a union man, he believed in “an honest day's wage for an honest day's work.” Still, his unwavering belief in meritocracy put him at odds with the union’s strict adherence to seniority. The union also protected people he thought were lazy, creating an unsafe work environment for all. He wasn’t into filing grievances, though, as tattling to third parties (a product of the north’s Culture of Dignity) is an affront to personal honor where men handle their own business “mano a mano.”

As the Industrial Age gave way and the Information Age took full root with the internet, my childhood may have been different. Not a chance.

Read Part 2.