Ordways: A History of Labor - Part 2 of 2

Dad’s lessons in the yard and in the mill

Robert Ordway, The Fourth Turning that never came

Unlike my peers, my childhood was “distinctly southern.” There were no written house rules, but expectations were made clear with “Boy, don’t make me tell you twice,” and I often referred to Dad as “sir” in our conversations.

Unlike the beatings from other subcultures, the threat of violence from a belt or paddle was sufficient for behavior correction. During my summer visits to Kentucky, Papaw had me pick out my own switch on a few occasions. He started skinning the branch with his pocket knife, but it was never used.

Dad morphed a southern phrase, “that burns me up,” into “that burns my ass.” Both he and Papaw would roll their tongue and bite it, which usually meant a ‘head thumpin’ (flick) was en route. They called them “attention getters,” which were quite effective.

There were no chore lists, just the expectation to help dad with whatever needed to be done. He often called the one-offs “projects”. When you don’t come from money, the ability to hire out work is a rarity. This led to dad’s often-used phrase, “Son, figure it out.”

Yardwork started at an early age with mowing, weed eating, and caring for two large outside dogs. This was intermingled with 4x4 wood stacking for the fire pit, trimming trees, controlled burns behind the fence (which always got the fire department called out), cleaning gutters, and quartering deer in the garage, among other things. We also ‘tinkered’ with anything mechanical like cars and lawnmowers. Dad enjoyed watching the tiller drag me along on the first few passes in the Spring before we planted the seasonal garden. Months later, routine weeding would ensue. I even had to drag a 55-gallon trash can that weighed more than me from behind the garage, down the driveway, and to the street each week.

If friends stopped by, Dad would put us to work, and I always tried to convince them to stay: the faster we got things done, the sooner we could play. I was never paid an allowance, but Dad never let a real need go unfulfilled. He said no to about 99% of my requests with a firm, “Don’t ask me again.”

Papaw fell away from the church after migrating north, and Dad didn’t engage the spiritual world until after he got ALS, despite the many religious items hanging in our house. The union did not replace their religion, but the brotherhood is well captured in the chapter Steel Family Memories and the Culture of Unionists in Striking Steel. Dad’s friend group was small, but loyalty was everything to him. (another cultural concept of southern honor). Dad learned that virtue from Papaw, who invited over men (often times black) and worked on their cars while refusing to charge them anything. That sentiment is well stated in Black Freedom Fighters in Steel where Gary Sheet & Tin interviewee, George Kimbly (a black man) said, “People helped each other, and a guy would come up to you and ask you for a dime or a nickel, and it you had it, you’d give it to them, white or black.”

In 1996 and 1997, we helped two Hungarian brothers build houses (yes, I know exactly where I was when Tupac was killed). I recall my dad saying, “Don’t stand around with your hands in your pocket,” which led to another principle: “Son, never stand around and watch another man work.” He believed every man should get his hands dirty, and once made fun of me for having soft hands. If you’ve ever met a steelworker, the years of labor turn their fingers into thick calloused sausages. We spent a few times at one of their new houses turning deer into sausage links, a laborious activity in its own right, where I learned pig intestines were used as casing.

Many Americans talk about their rights and privileges, but never the implied duties and responsibilities my Dad often spoke about when it comes to how we ought to live and treat others in civil society.

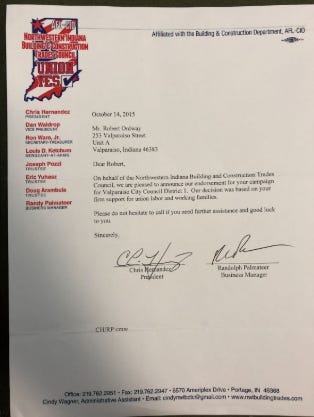

In junior high, the building trades and IBEW came to my junior high, and given how much I loved RC cars, I was convinced that I’d become an electrician. It was a profession where I could utilize both my hands and mind, without worrying about the outsourcing that was happening. After dad was diagnosed with ALS, thinking about what I wanted to do with my life all but stopped as we went into survival mode. Interestingly enough, the trades would endorse me for local office nearly 20 years later.

After his disease took full root, dad’s forced voluntary hardship in the early years prepared me mentally and physically to handle anything that might come my way. I now had to run our outside operation and was fully prepared, or so I thought…

In my junior year, I forgot to put oil in our new John Deere tractor, and it blew up after one pass around the yard. That summer, I had to push-mow and bag the clippings, which took hours each week. In fashion, Dad said, “Son, you only need to learn once.”

It was this blue-collar, working-class upbringing and countless hours spent with Dad outside that developed my mechanical aptitude and spatial reasoning. It led to a high score on the ASVAB and non-stop calls from the military after 9/11, where I eventually signed up for the U.S. Navy’s Delayed Entry Program.

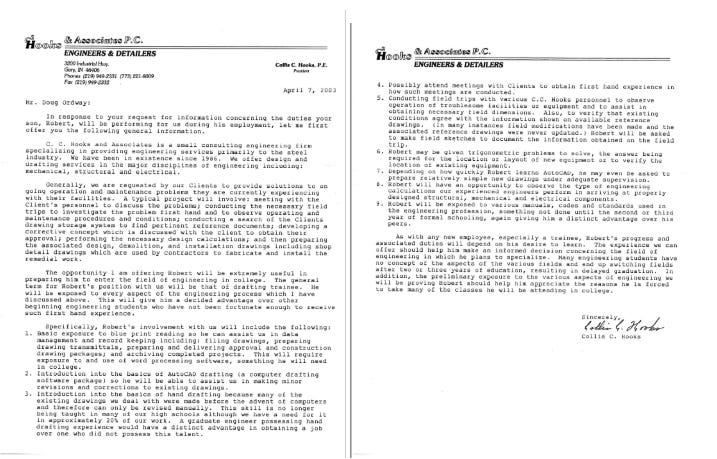

After I was awarded the Lilly Endowment Community Scholarship, going to war in Iraq, which had just started, was off the table, as it was clear I was going to college. My chemistry teacher offered me the opportunity to work for her husband, Mr. Hooks, who owned an engineering firm that serviced the local steel mills.

Knowing that I would spend time in the mill, I thought it was counter to everything Dad had taught me. Luckily, most of my work was done in the office, where I focused on design and detail work, including drafting and CAD.

I was afraid to leave my dad’s side (that loyalty thing), so to avoid this opportunity, I cooked up a lie that my dad needed a letter to know what I would be doing. It completely backfired. When I showed it to him, he said, “Son, looks like you have yourself a job!” The school let me skip nearly two classes a day, my last semester of senior year, for work. Some kids were upset that I got to leave to ‘make money.’

I spent 2003-2015 working full-time in the summers and part-time in college/grad school as a contractor for Indiana Harbor Works, which underwent several ownership changes during my tenure. The experience in various parts of the mill gave me a deep respect for the folks who were employed there. Laboring day to day in a mill is best captured by my fellow Millennial in Rust: A Memoir of Steel and Grit (2020), who spent a few years at Cleveland Cliffs during the Great Recession.

I did not appreciate Dad’s words of wisdom until nearly a year after he died, when I transferred to Valparaiso University and read Studs Terkel’s Working (1974) as part of the core curriculum. I was triggered by the interview of a worker from U.S. Steel, Steve Dubi – “I told my sons, ‘If you ever wind up in that steel mill like me, I’m gonna hit you right over the head. Don’t be foolish. Go get yourself a schooling. Stay out of the steel mill or you’ll wind up the same way I did.’”

His son, Father Leonard Dubi, reiterated those sentiments in the following interview - I know my father had much more potential, but he was locked into a system day after day, and he didn’t want to see me get locked in. He encouraged me to go to college ”to make something of yourself” were the words he used.

It was the same sentiment that led to the demise of a union reformer's campaign in Northwest Indiana. Ed Sadlowski ran to represent District 31, but his campaign was hurt by an interview for Penhouse magazine where he commented that he didn’t want his children to be steelworkers and that no one should work in a steel mill.

In many writings, there are many mentions of the ‘golden handcuffs’ put on the men who worked in the mill,but they couldn’t get out because the money was too good. Some get trapped by the ‘overtime game’ as they choose a lifestyle of fancy boats, lifted trucks, or just love a big bank account.

In I'll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition, (1930), the 12 contributors repeatedly state their concerns about endless labor in the industrial north, leading to a worship of consumption and indulgence. I think they are right. I am fortunate that both dad and papaw were never driven by materialism and rarely worked more than 40 hours, so they could enjoy time with family or pursue hobbies. Many steelworkers might acquire a generous pension, but rarely live long enough to enjoy it. Dad also said, “You can always make more money, but you can never get back time.”

I fulfilled Dad’s wish and became the first in the family to complete my undergraduate degree in Finance in December 2007, but it was nothing short of theory rooted in ‘free market fundamentalism,’ where all that mattered was ‘maximizing shareholder value.’ Workers were reduced to mere numbers on an Excel spreadsheet in one of my classes called cost accounting.

The Great Recession led me back to graduate school, where I completed my master’s degree in International Commerce & Policy in August 2010. It was here that my upbringing was vindicated. The theory of “comparative advantage," where countries benefit by specializing in certain goods and services, makes sense, that is, until you learn how governments subsidize industries, steal intellectual property, and practice unequal standards when it comes to labor and environmental protections.

Given the complex history of labor in America, many would be well served to read the 674-page book, There Is Power in a Union: The Epic Story of Labor in America. With that, my views always have and will remain highly nuanced in the space despite the simpleton’s binary approach in Washington, D.C.

Today, I look back at the labor rituals I performed at home, in line with the many Ordways that came before me, along with the organized labor within the steel mills that provided my family with a path out of western Kentucky, where the population and economic opportunities peaked in 1900. Steel completely changed human civilization during the 20th century. I honor this multi-racial working class and their labor with the title of my memoir, Millrat.

Dad didn’t read much outside of the local newspaper. Still, he would have agreed with Frederick Douglass’ quote, "It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men." (1855) In addition, dad implicitly practiced and taught me to embrace President Teddy Roosevelt's lifelong philosophy of The Strenuous Life.

While they say good times make weak men, I am here to report that my childhood in the 1990s was indeed a time of good times, but that didn’t stop Dad from making me into a hard man.