The Vance-Ordway Parallel: Part 1 of 2

The Iraq War and Great Recession Generation

Introduction

In The Elder Millennial Memoir, Parts 1 and 2, I covered how J.D. Vance was the inspiration for finishing my book back in 2016, as well as the digital tools it took to complete a first draft. As an addendum, I included a list of Millennial Memoirs that have kept me inspired.

This post builds on that and explores the unusual high number of parallels between J.D. Vance and me from years past. Both our political and religious worldviews were highly shaped by the family and friends around us, along with national affairs of the day.

The Iraq War

J.D. Vance is six months older than I, and we both graduated high school in 2003, just months after the Iraq War started. Seeing 9/11 live is a defining moment for our generation, and I attribute our family’s culture for compelling us to join the military (p. 156) as Ordways have fought in every war since the Revolution. Then, and to this day, DC politicians have said the only way to move up is through college (p. 244). We both came from subpar schools, but we can attest that the teachers did everything they could to help us succeed, given the limited resources and circumstances beyond their control (p. 244). We were burdened with the idea of school debt and financial aid forms, as well as moving to a new world (p. 156). Still, Vance admitted he joined the Marines because he wasn’t ready for adulthood (p. 177). His family said he wasn’t a good fit for the military (p. 157), while my Dad said I was “too smart” to join.

Shortly after 9/11, I took the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) as my high school was one of the few places where it was forced upon all juniors. It was the only test I ever enjoyed as Dad’s blue-collar parenting prepared me for the electrical, mechanical, and woodshop sections that were foreign to most of my peers. I should have done better on this exam, but it was also during a time when my Dad’s ALS was getting bad, and mom’s bipolar disorder drove family fights that lasted all night, every night.

Not long thereafter, all four branches would be calling my landline phone, offering sizable signing bonuses. Some would show up at my house unannounced. I visited the Military Entrance Processing Station (MEPS) in Chicago and enrolled in the Delayed Entry Program (DEP) for the U.S. Navy. Vance’s notes, “...mom wanted us to be exposed to people of all walks of life.” (p. 64). My mom beat a similar drum as a Navy Reservist, and said, “The government paid me to see the world, and I got to work with all kinds of people.” Between us, only Vance would be the one to get such an experience. (p. 160)

Both Vance and I had serious reservations about joining, and they centered on family. He knew his mamaw was on borrowed time, and she might pass during his service (p. 158) as he was taught “[mamaw] loathed anything that smacked of a lack of complete devotion to family” (p. 41). Likewise, my Dad was in year five of ALS and the idea of leaving his side was unbearable. My loyalty to him superseded my loyalty to the country.

Shortly after Mom left for the Iraq War in March 2003, my life changed overnight when I was awarded the Lilly Community Endowment Scholarship, which covered full tuition for four years at any Indiana university or college. The program was started because of the “brain drain” in Indiana, something also described by Vance about people becoming educated and leaving their home communities for good. (p. 180).

Vance would receive a scholarship years later that also changed the trajectory of his life, sending him to Yale Law School. (p. 199). We were both awarded purely based on socioeconomic status and the challenges of our lived experience.

Vance and another millennial author, Rob Henderson (Troubled, 2024), attribute the military for providing the structure and order they needed to be productive members of society. (p. 174) Vance says, “It was the Marine Corps that gave me the opportunity to truly fail…” (p. 175).

Dads

Vance had a revolving door of father figures (p. 88), but says he was surrounded by caring men who made a difference (p. 239). I had the same male support figures when I was a vagabond between Virginia and Kentucky, age 0-4, and after grad school when I became engaged in local politics.

Unlike Vance, I didn’t need the same structure or discipline from the military because Dad raised me in old Kentucky ways, a blend of a Culture of Honor and The Agrarian Tradition. Great grandpa, Papaw, and all his siblings served in some capacity, so unprecedented levels of “order” were a family affair as I often referred to my Dad as “Sir.”

Even though he didn’t serve in the military, Dad acted like it. There was order, routine, process, and no back talk. Like basic training, Dad didn’t need force because he knew how to get into my mind. The fear of getting hit was more than sufficient, but every once in a while, a ‘thump on the head’ was a primary ‘attention getter’ as he called it, something passed down from Papaw.

Vance says we have “.. a peculiar crisis of masculinity” (p. 5) as a societal issue, with “too many young men immune to hard work.” (p. 5). I couldn’t agree more as I witnessed a similar passivity by peers from challenged backgrounds. I’m thankful for the high expectation of a strong work ethic, a framework Dad instilled from generations handed down.

Vance received a BB gun from his papaw. (p. 106) which paid dividends to Vance as a serviceman. (p. 105). Likewise, Dad bought me a Red Ryder, and it became a useful tool to teach me personal responsibility and a deep respect for weapons. I bonded with my Dad from reruns of Terminator 2 on a cheater box acquired through steel mill buddies while Vance watched the same with his mamaw (p. 166).

Falling Apart

For Vance, things began to unravel when he was nine (p. 70), and for me at 13. He moved around a lot as his mom changed boyfriends while I was trying to internalize my Dad’s new disease, which led to us both acting out at school (p. 95). Our grades started to slip, but we couldn’t tell anyone what was going on (p. 72). Our mothers forced us to meet with a therapist, and we saw them purely as obstacles (p. 120). Given that my mom worked in the school system, she had the counselors ask me specific questions and then shared my responses with the world, causing me to shut down on everyone. Vance’s mamaw said, “You never talk about family to some stranger. Never.” (p. 41). I followed the same ethos by bottling up everything inside which leads to all kinds of negative externalizes that arise in various ways years down the road.

Vance notes southern culture with “Family, friends and neighbors would barge into your home without much warning.” (p. 32). Foreign to a northerner like Mom, my next-door neighbor and great grandma, a 1970s Kentucky migrant, would do the same. Mom would berate her for being nosy and not “respecting our family’s privacy” (ironic given her gossip). Vance mentions his health issues from the trauma (p. 72), whereas mine were weekly migraines that lasted for years until my Dad’s passing.

Moms

Our moms were good people, but a major source of our early challenges. They had erratic behavior, so I can relate to “Never speak at a reasonable volume when screaming will do.” (p. 71). They both thought money was deemed affection (p. 136). My mom worked side jobs to buy my TI-89 for advanced math, whereas Vance’s mamaw sacrificed dinner to buy his. (p. 139) They both bent over backwards to make sure we had “a nice Christmas” regardless of financial situation (p. 251).

His mom would make up for her emotional volatility by buying him football cards (p. 76), whereas I got whatever was on my list that Dad said no to previously. Our moms took us to church on the rare occasions when they thought we needed religion. (p. 86).

Our moms also used selective stories to weaponize men against us. Reconnecting with his biological father, Vance learned the truth about why his parents split (p. 94). My mom often dug up my Dad’s past youthful shortcomings, and she had nothing positive to say when I discovered who my biological father was at age 22. From then on, explaining my family story including half-sisters with different last names has been complicated, something Vance has dealt with his entire life. (p. 80).

Responses to death are highly charged events for our moms. Vance’s mother became cold and possessive to the family when his papaw died (p. 112), and when my uncle committed suicide, my mom also claimed their relationship was “extra special,” so no one should be grieving like them. When Vance’s mamaw died, what little she had was split between him and his sister (p. 170), the same for my sister and me when our Dad died in 2003.

At some point, Vance and I couldn’t take it anymore and exploded. Vance belittled his mom when she asked for his pee so she could pass a drug test for work (p. 120). My mom said some of the nastiest things to my Dad while he was dying (saving exact verbiage for the memoir). One night, I popped out of bed, held her throat against the fridge with my arm cocked, but never threw the punch. My Dad subsequently yelled at me the next day as he said, “Never hit a woman.” Even though I didn’t, he thought my level of aggression toward her was unacceptable.

Both of our mothers had an appreciation for education (p. 64), took us to the public library to get books (p. 60). I read every Goosebumps book published to get free pizza from BookIt! Program. They completed our science fair projects to perfection without our consent (p. 65), but in many ways we can attribute part of our success to the seeds our mothers planted early on. They knew education was the way up and out.

Vance acknowledged that he never tried to sympathize or understand his mom (p. 231), and neither did I, but we both came around after we had our own personal circumstances figured out. To better my environment, like Vance, I also refused to live with my Mom after my first year of college, after Dad passed away, and instead, moved into the basement of my then-girlfriend’s parents’ house.

Vance’s mom had a failed suicide attempt (p. 74), but I’m happy to see she eventually overcame her drug addiction. My mom, on the other hand, could not overcome her challenges with bipolar disorder and took her life in 2009. In the end, I think Vance and I both tried to blend the right amount of compassion and accountability to the best of our ability when dealing with our mothers.

The Savior

In high school, Vance’s GPA dropped to 2.1 at the end of his freshman year (p. 127) while I landed a D on my permanent record in Chemistry halfway through my sophomore year. I began drinking in the garage during Dad’s six-month stay (Christmas 2000) with my widowed mamaw, who’d relocated an hour south of our house in 1997. After witnessing his decline during visits, I planned out my own suicide.

Vance and I needed a savior.

We attribute our “three years of stability” (p. 138) to one person. For Vance, it was moving in with his mamaw, who gave him three rules: Get good grades, get a job, and “get off your ass and help me.” (p. 133). It was a loose but non-negotiable framework also delivered to me by my Dad. Neither of us had a set chore list (p. 133), but I can say, even after he got sick, Dad always had ‘projects’ that interrupted my time with friends. Vance got a job at Dillman’s grocery store (p. 138) while I worked at a Polish Catholic reception hall. That work ethic and financial need forced both of us to hold two jobs (and at one time three) in college (p. 182).

In his work, Vance noticed that people gamed the welfare system (p. 139), but I recognized that much earlier in first grade when a friend raised by a single mother had a “free lunch” ticket (marked by color), yet got the new Shaq Attaq shoes while my family shopped at PayLess for the school season (imitation LA Lights were $19). This also happened with each new video game system that came out through the 90s, the poorest kids always seemed to have the newest stuff.

My stability came just weeks before my Dad moved back into the house in March 2001. I started dating a girl who stopped me from killing myself, was always encouraging, and provided a non-judgmental sounding board when it came to my family problems. Her visits to my house after school also helped to stifle fights between my parents, which were often initiated by Mom. With my girlfriend there, mom couldn’t be seen participating, a method to control her side of the narrative to the outside world.

I never got below a 4.0 from that point on and went from the bottom of my class to the Top 10. She got me out of “metal head” black clothes of depression and turned me into a walking ad for Old Navy. She is the reason I am alive today.

Kentucky

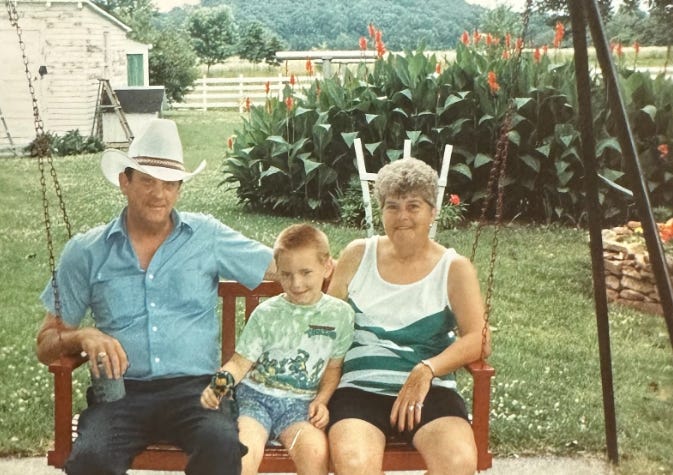

Vance identifies with the Appalachian migrants (p. 3), calls himself a hill person (p. 22), and says he will always think of Jackson as home (p. 18). Culturally, I, too, think of myself as a Western Kentuckian. Both Vance and I spent summers visiting our grandparents in Kentucky until we were 12 (p. 12), called them mamaw and papaw (p. 23), spent a lot of time on porch swings (p. 12), and stopped for the passing hearse when neighbors died (p. 12) out of respect. His family used phrases like “too big for your britches” (p. 30), as did my mamaw when I was “acting smart.” During a recent visit to Kentucky, one of my grandparents' old neighbors quoted my Papaw’s sentiments about me, “That boy might be too smart for his own good!”

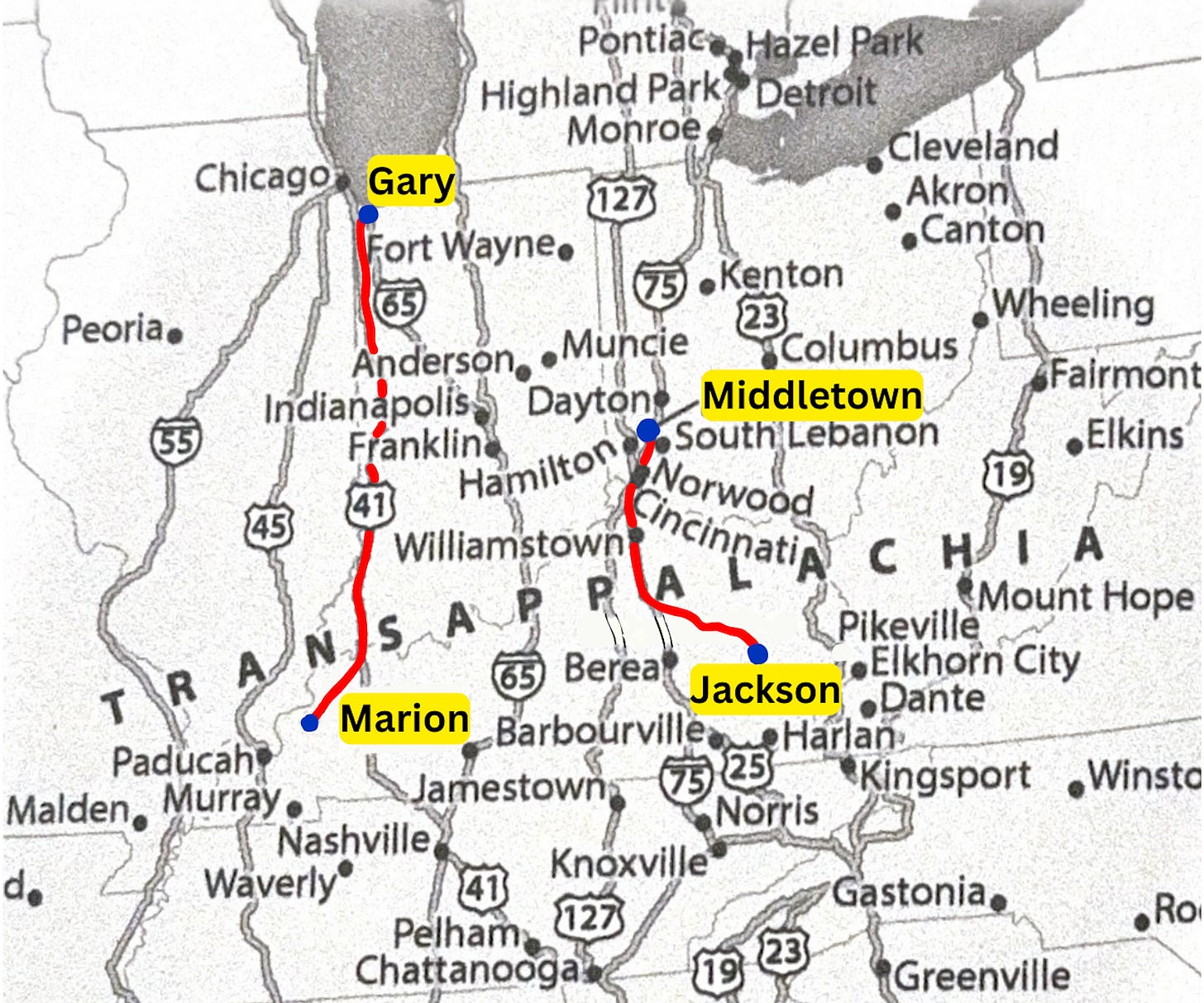

Our grandparents migrated up hillbilly highways (p. 28) a decade apart and from opposite ends of the state. Armco in Middletown, Ohio, was an economic savior for his grandparents (p. 55) just as U.S. Steel in Gary, Indiana, was for mine. They both returned to Kentucky often out of a sense of duty (p. 124), went south for the holidays (p. 29), believed in an “...intense loyalty, a fierce dedication to family and country,” (p. 3), and “... had an almost religious faith in hard work and the American Dream.” (p. 35) My grandparents’ visits home are well tracked in The Crittenden Press, whose archives go back to 1879. They are now accessible online.

Vance’s papaw was a Democrat because it was the “party that protected working people” (p35), but mine was a Republican because Crittenden County was a cultural anomaly in western Kentucky during and after the Civil War. Research says that is because of its close ties to Cave-In-Rock, Illinois, and President Lincoln. Despite many residents owning slaves, Crittenden emerged as the most pro-Union county in the western Pennyrile region.

Other than Mamaw saying, “well shitfire,” my grandparents cussed a lot less but would have agreed with Vance’s mamaw, “Never be like these fucking losers who think the deck is stacked against them.” (p. 36). This outright rejection of victimhood culture while illustrating the importance of family and community is part of our shared identity and leads into my next post, which will feature a cultural analysis of his book. In addition, I’ve provided all the books (but not online research) used to better understand southern migration in the 20th century along with his work.